The Aldar Playbook

Inside Abu Dhabi's $20B Real Estate Empire

While Dubai's developers were making global headlines with palm-shaped islands and the world's tallest towers, something more interesting was happening 150 km’s down the E11 highway.

Aldar Properties has quietly assembled one of the Gulf's most formidable real estate machines - now worth $20B, with 2024 profits up 47% to AED 6.5 billion.

Over the past five years, while everyone was watching Emaar's international expansion and DAMAC's luxury pivots, Aldar's stock has climbed over 350%. Not through flashy projects or celebrity partnerships, but through something far more valuable: building a structurally advantaged business model that only they can execute.

The question isn't whether government backing guarantees success - plenty of state-backed developers have failed. The real question is:

What makes Aldar different, and can anyone else replicate what they've built?

How Aldaar Started

The Abu Dhabi Answer (2005-2007)

Aldar's story begins with a strategic gap. In 2005, while Dubai had Emaar executing its vision, Abu Dhabi lacked a comparable development vehicle. Founded in 2004, and immediately listed on the Abu Dhabi Securities Exchange, Aldar was structured differently from the start - a public-private hybrid designed to balance government objectives with market discipline.

The early projects revealed the scale of ambition. Yas Island wasn't just a development - it was Abu Dhabi's statement of intent, anchored by a Formula 1 circuit.

The circular Aldar HQ building became an architectural icon. Al Raha Beach created an entirely new waterfront district. By 2008, the company was reporting 203% revenue growth.

The Testing Years (2008-2012)

Then came the crisis. While Dubai's property market crashed over 50%, Abu Dhabi's decline was more contained but still severe. Aldar faced a choice: fail like dozens of other developers, or fundamentally restructure.

Between January 2011 and December 2011, the company received approximately $5 billion in government support. But this wasn't a bailout in the traditional sense. The government purchased strategic assets - Ferrari World, Yas Island infrastructure, Central Market - while Aldar retained operational control. This asset recycling created the template for the partnership model that drives the company today.

The 2013 merger with Sorouh Real Estate ($19B at the time - one of the largest UAE developers) doubled Aldar's scale overnight, consolidating Abu Dhabi's development sector under one entity.

The Pivot to Recurring Income (2013-2019)

Post-crisis, Aldar made a fundamental strategic shift. Instead of just developing and selling, they would develop and hold. The 2018 launch of Aldar Investment formalized this strategy, creating a dedicated platform for recurring income assets.

New business lines emerged: Aldar Academies in education, Provis in property management, retail through Yas Mall. Each vertical added stable, predictable revenue streams that smoothed the cyclical development business.

The Modern Platform (2020-Present)

COVID tested the new model - and it held. Unlike 2008, Aldar needed no government rescue. The company used the crisis to accelerate, not retreat.

The 2021 acquisition of 85.5% of Egypt's SODIC for AED 1.5 billion marked the beginning of international expansion. The 2023 purchase of London Square for £230 million brought Western market expertise. Alpha Dhabi's consolidation of control in 2022 clarified the ownership structure.

The September 2024 Mubadala joint venture worth AED 30 billion represents the evolution of the government partnership model - strategic co-investment rather than support. With record sales of AED 33.6 billion in 2024, Aldar has transformed from crisis survivor to market leader.

Now we understand the story, let’s look at why Aldar remains strong in the market.

What Makes Aldar Work

The Partnership Paradox

The lazy analysis of Aldar goes something like this: "It's government-backed, so of course it succeeds." This misses the sophistication of the model entirely.

Aldar's government relationship isn't a blank check—it's a carefully structured alignment of interests. The company is controlled by Alpha Dhabi Holding, itself a quasi-sovereign entity, with additional stakes held by Mamoura Diversified (25.12%) and other government-linked entities. But ownership is just the beginning.

The masterstroke came in September 2024 with the AED 30 billion Mubadala joint venture. Aldar holds 60%, Mubadala 40%. This isn't a bailout or a subsidy - it's strategic co-investment. Mubadala brings land and patient capital; Aldar brings execution and operational excellence. Both share in the upside.

The partnership leverages Mubadala's land bank and institutional strength with Aldar's development and asset management expertise - this isn't bailout dependency, it's strategic alignment.

This model was stress-tested during the 2008 financial crisis, and the results are instructive. Yes, Aldar needed approximately $5 billion in government support between 2011 and 2012. But look closer at how it was structured: the government didn't just write checks. They purchased strategic assets - Ferrari World, Yas Island infrastructure, Al Raha Beach properties - at attractive valuations.

Aldar kept operating these assets, maintained cash flow, and rebuilt its balance sheet. The government got hard assets, Aldar got liquidity, and both parties aligned for the long term. Compare this to the Western bank bailouts of the same era, where taxpayers got IOUs and banks got cash…

Fast forward to COVID-19, and Aldar needed no government support. The model had evolved from dependency to symbiosis.

The Dual-Engine Design

Most real estate developers face an existential choice: develop and sell for quick profits, or build and hold for steady income. Aldar chose both.

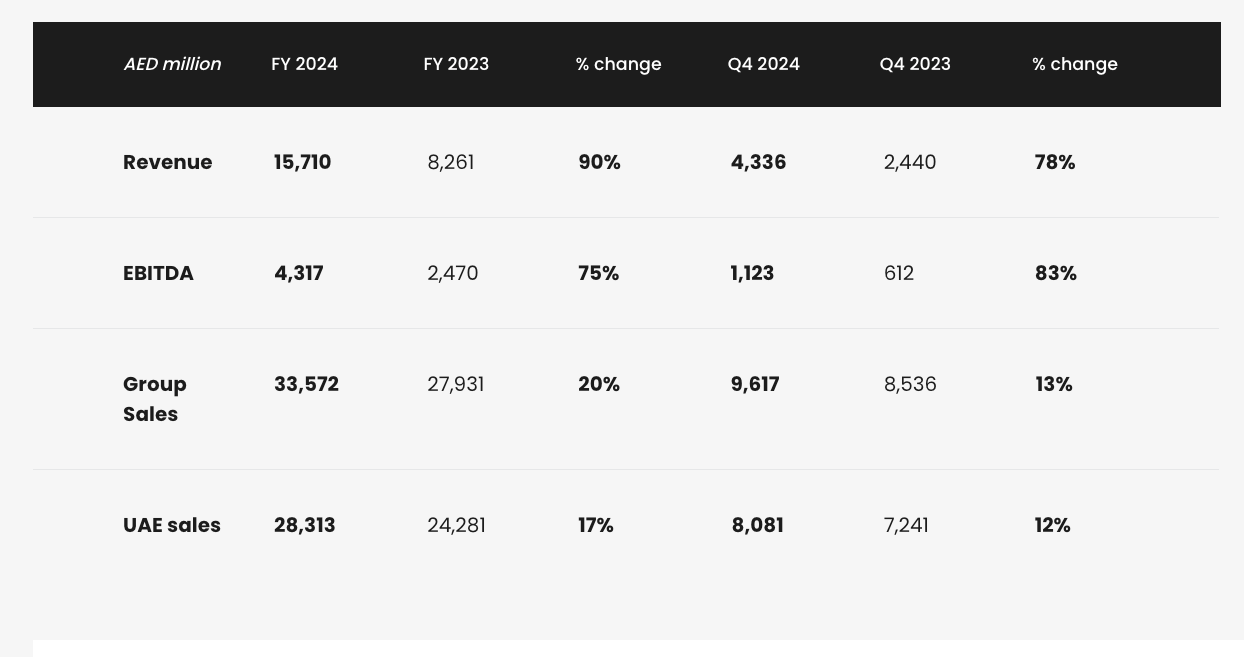

The company operates through two distinct but synergistic platforms. Aldar Development generated AED 15.7 billion in 2024 revenue (up 90% year-over-year), handling traditional property development and sales. Meanwhile, Aldar Investment pulled in AED 7 billion (up 21%), managing recurring income assets.

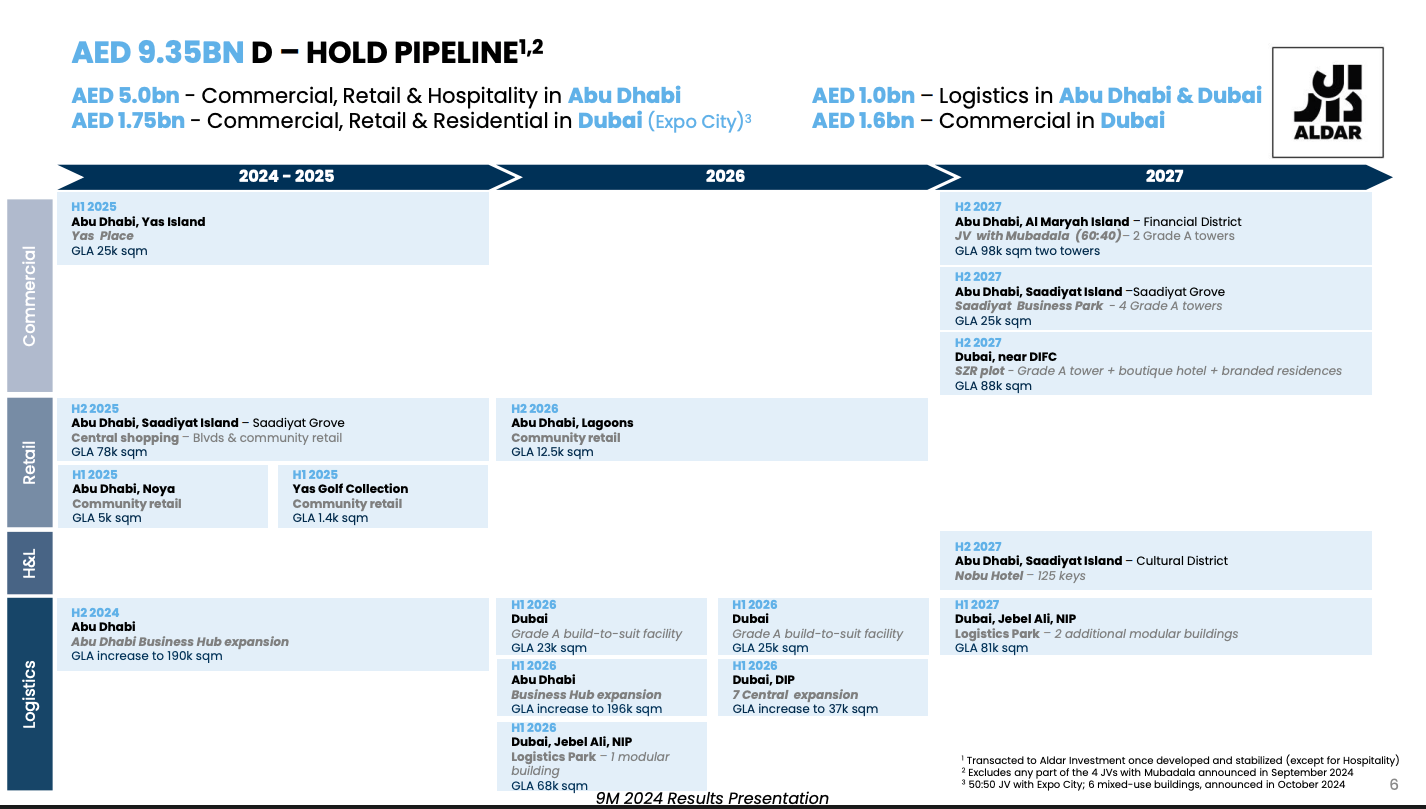

But here's where it gets interesting: Aldar is systematically moving assets from the development side to the investment side through what they call their "develop-to-hold" (or D-Hold) pipeline. This pipeline has expanded from AED 9.35 billion to AED 13.3 billion in just one quarter.

This is a great model that, personally, I like to see. They develop at their own cost of capital, capture the development margin, then hold the asset for recurring income. No need to pay market prices for acquisitions. No bidding wars with other investors. They manufacture their own inventory.

The portfolio breakdown reveals the strategy:

AED 5.0 billion in commercial, retail, and hospitality in Abu Dhabi

AED 1.75 billion in mixed-use through the Expo City Dubai joint venture

AED 1.6 billion in Dubai commercial

AED 1.0 billion in logistics across both emirates

Yas Island: The Billion-Dollar Experiment That Worked

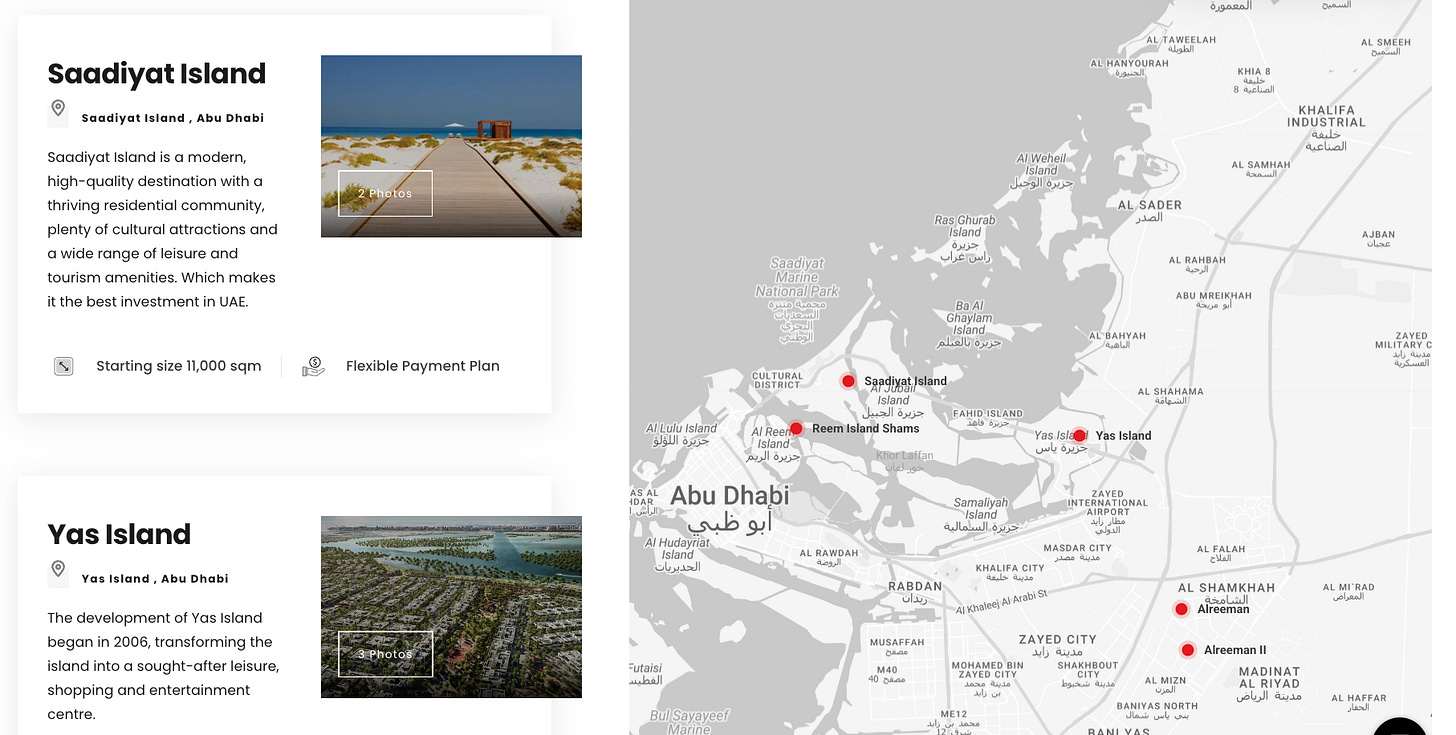

If you want to understand Aldar's competitive advantage, spend a day on Yas Island. What started as a Formula 1 circuit and theme park has evolved into something far more sophisticated: a fully integrated live-work-play destination generating 6-7% rental yields on apartments.

The recent Waldorf Astoria Residences launch tells the story. All units sold on launch day for $231M in total, with 76% going to international buyers. Buyers are paying premiums for a proven ecosystem.

Yas Island demonstrates Aldar's core competency: destination development. They don't just build buildings; they create micro-cities with their own gravitational pull. The Formula 1 track brings global attention, the theme parks drive tourism, the hotels capture visitor spending, and the residential communities house the workforce that makes it all run.

More importantly, it's proven the model can be replicated. Saadiyat Island focuses on culture (Louvre Abu Dhabi, Guggenheim coming soon), while Al Raha Beach targets lifestyle and waterfront living.

The International Expansion Reality Check

The AED 1.5 billion acquisition of 85.5% of SODIC in Egypt (alongside ADQ) wasn't about geographic diversification - it was about replicating their government partnership model in a new market. SODIC contributed AED 701 million to group revenue in 2024. Not massive, but it's a foothold in a 100-million-person market where the same playbook - government relationships, master-planned communities, patient capital - can work.

The £230 million acquisition of London Square in the UK serves a different purpose. With 3,500 completed homes and a £2 billion pipeline, it's Aldar's laboratory for competing in developed markets without government support. If they can make the model work in London's hyper-competitive, highly regulated market, they can take it anywhere.

But here's what's smart: Aldar isn't trying to be a global company. They're an Abu Dhabi company with selective international investments. The core business - the government relationships, the land bank access, the destination development expertise - stays in the UAE.

The Technology and Operations Edge

Aldar's advantage comes from vertical integration. They don't just develop—they manage (through Aldar Estates), they invest (through Aldar Investment), and they operate (through various subsidiary platforms). Each vertical feeds intelligence back to the others, creating a learning loop that independent developers can't match.

The capital structure reinforces these advantages. With an AED 9 billion revolving credit facility, USD 1 billion in hybrid notes, and a recent USD 500 million hybrid capital solution from Apollo, Aldar has the firepower to move fast when opportunities arise. The Moody's Baa2 credit rating means they borrow at rates most regional developers can only dream of.

Where the Model Struggles

The Sovereign Risk Premium Nobody Prices

The 66% to 78% reliance on international and expat buyers intersects dangerously with Abu Dhabi's economic structure. Unlike Dubai, where non-oil GDP comprises 95% of the economy, Abu Dhabi still derives substantial fiscal revenues from hydrocarbons.

Consider the transmission mechanism: oil price decline → fiscal tightening → reduced government investment → fewer jobs → expat exodus → property oversupply. Aldar sits at the end of this chain, magnifying rather than diversifying the underlying commodity risk. Their government partnership, rather than providing countercyclical support, could amplify the downturn as both parties face the same macro headwinds.

The Institutionalisation Trap

The evolution from entrepreneurial developer to quasi-state entity creates specific pathologies. The 2011-2012 period required $5 billion in government support structured as asset purchases. While Aldar retained operational control, the precedent was set: the company is too strategically important to fail.

The AED 54.6 billion backlog represents 2.4x annual revenue - a massive execution burden that assumes perfect coordination across design, construction, sales, and delivery. Private developers facing similar execution risk would maintain smaller pipelines or higher margins. An organisation in Aldar’s position could lean too heavily on the confidence of state backing.

The Mubadala partnership worth AED 30 billion illustrates this dynamic. Mubadala provides land, Aldar provides execution, both share upside. But who bears downside if projects fail?

The Scalability Paradox

Aldar's international ventures expose a fundamental limitation: their competitive advantages are non-transferable. SODIC contributed AED 701 million to 2024 revenue - 3% of the total despite representing a major strategic initiative.

The failure isn't operational - SODIC is profitable. It's structural. Aldar's UAE model depends on vast amounts of comfortability within the local market. This could create a growth ceiling. With Abu Dhabi's population at 4 million and growing at 2-3% annually, Aldar will eventually saturate their core market. International expansion is necessary for continued growth.

The Complexity Multiplication Problem

Vertical integration at Aldar's scale creates non-linear complexity. They're simultaneously managing property development, asset management, retail operations, hospitality, education, and property management. Each vertical has different working capital requirements, regulatory frameworks, and operational rhythms.

The 49 contracts worth AED 22 billion awarded in 2023 suggests impressive execution capacity. But it also reveals coordination complexity that would challenge any organisation. A 10% cost overrun - not unusual in construction - represents AED 2.2 billion in additional capital requirements. A six-month delay cascades through the entire development pipeline.

Traditional developers can fire underperforming contractors, switch suppliers, or pivot strategies. Aldar's integration means problems must be solved internally. When your property management division underperforms, it affects your development sales. The same integration that creates margins in good times amplifies problems in bad times.

The Demographic Time Bomb

The 78% international buyer composition masks a deeper vulnerability. Often, these aren't permanent residents but transient professionals whose tenure in Abu Dhabi averages 4-7 years. They're buying investment properties, not homes.

This creates a specific risk profile. Investment buyers are momentum traders - they buy rising markets and flee falling ones. Unlike owner-occupiers who might accept paper losses to maintain lifestyle stability, investors have no emotional attachment to Abu Dhabi property. A 10% price decline could trigger a 30% increase in listings as investors rush to exit.

The Next Decade: What Aldar Tells Us About Real Estate's Future

The Recurring Income Transformation

Aldar's develop-to-hold pipeline has expanded to AED 13.3 billion, but the target of 40% recurring income reveals a deeper strategic shift.