Dubai's Developers Are Leaving Billions on the Table

Western markets cracked the code on institutional rental housing a decade ago. Dubai has superior demographics but refuses to see what's sitting in plain sight.

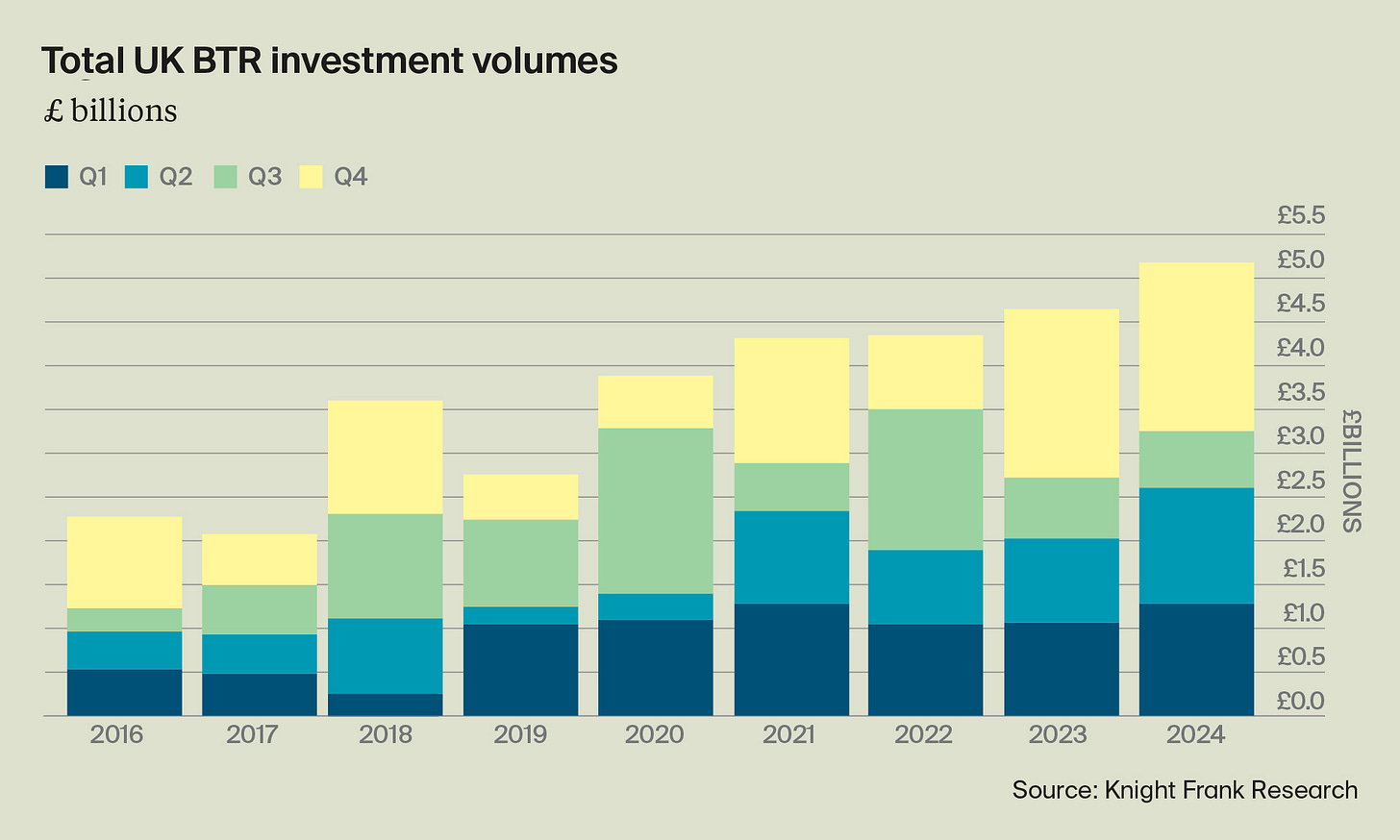

The UK build-to-rent sector crossed £5.2 billion in investment for 2024, marking its fifth consecutive record year. Meanwhile, the global coliving market hit $7.82 billion, with projections showing it will double to $16.05 billion by 2030. Coliving spaces in US urban markets are generating 40-50% more rental income than traditional apartments.

What about…